On textiles (and a book review)

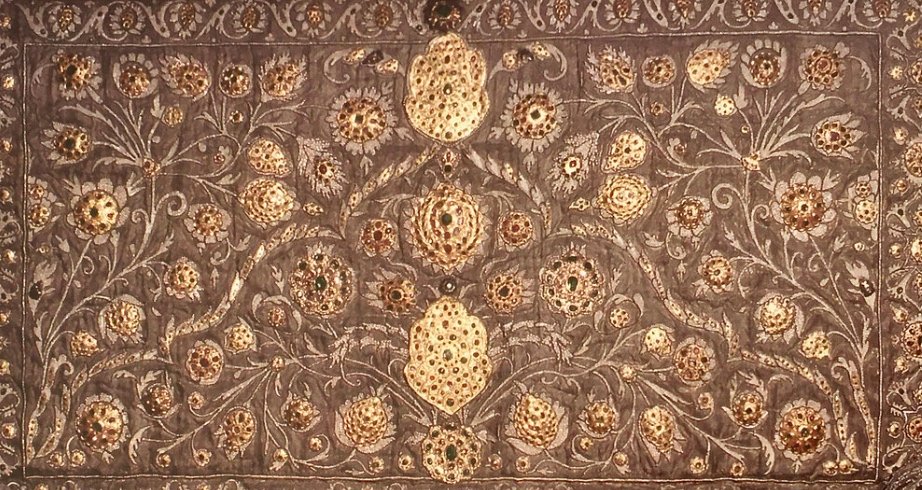

It’s funny how the world works. In June of 2021, Susan Scollay published a commentary on my book about Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmed II, praising it generously (**) but also calling me out for having labeled the textile hanging before Sultan Mehmed a “tapestry.” Her essay, in Emporium, an Australian research hub dedicated to the “cultures of luxury and consumption,” is a scholarly correction of my terminology. A tapestry, I learned, is a very particular sort of weave, where the warp is completely covered by the weft. What we are looking at in Bellini’s portrait is in fact an embroidery, studded with jewels. Scollay titles her essay “A need for globally consistent textiles terminology” and easily proves her case.

(** her essay begins: From time to time a book will inspire us more than most, or convince us that the direction our own thinking has recently taken is worthwhile, or simply engage us in a thought-provoking historical story that is very well-told. Elizabeth Rodini, a distinguished art historian based in Rome, has achieved all this and more with her latest book . . . )

I no longer remember why I did not post the article on this website alongside other reviews (I do recall that she had kindly notified me in advance of the coming critique by email). Two possible reasons: the summer of 2021 was a challenging time for me personally and professionally and I simply had my head elsewhere; and/or I may have preferred not to advertise my ignorance about textiles. But I do know that, even if under informed, I had chosen the word “tapestry” with purpose. One of my beloved professors, the late Marvin Eisenberg, was a textile collector. He once informed me that the object in Bellini’s painting was not a “rug” but something else. (I must have been calling it a rug back then but I no longer remember; this was eons ago). Like Scollay, he knew his materials well and wanted greater precision. Lazily, perhaps, but also out of ignorance, I chose “tapestry” as a default and moved on. My apologies, Professor Eisenberg.

The funny thing about all of this is that, since returning to New York from Rome in August , I have finally returned to a practice that I had picked up about 15 years ago but had to set aside: weaving. I got out my four-shaft table loom, signed up for an intensive introductory course at the Textile Arts Center in Brooklyn as a refresher, and began again to weave. My ambition is to weave some of the beautiful mosaic patterns that I photographed obsessively while I was in Rome. When I showed Isa, my teacher at TAC, pictures of the mosaics, she told me that that sort of work might be better suited to a tapestry loom.

So there I was, pondering the differences in these techniques and thinking about whether I should gain mastery of my four-shaft loom before moving onto a tapestry model, when I stumbled again upon Scollay’s article. Not only does it offer a helpful explanation of textile techniques and history, but it also illustrates—just as my book intended—how following a single object, a small anecdote, or even a slim thread (sorry) can lead to unexpected worlds of understanding.

As to the the mosaics, the loom, and me: I have a deep envy of Edmund de Waal, not only for his brilliant writing on topics close to my heart but for the ways in which he has folded making (ceramics), historical research, and writing into a single, interconnected project. I have long wished I could do the same. I doubt I will ever get there, certainly not with his mastery, but the tapestry loom may be a start.

Above are a few pictures from this journey, left to right: details of Bellini’s painted embroidery; an Ottoman embroidery from the Topkapı Palace Museum and Scollay’s article; a Roman mosaic; and my first creation on the loom since I returned to it last month.